Floods and Droughts in Tulare Lake Basin

by John T Austin

A dry pasture near Alpaugh, July 7, 2014. Photograph by Matt Black

From the Preface: The following report began as an effort to understand the hydrologic cycles of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks, but it has turned into something even more important. The pages that follow provide priceless insights into an entire region: the Tulare Lake Basin of Central California. This distinct geographic zone contains not only the southern Sierra Nevada with its twin national parks but also major cities, a significant part of the richest agricultural area in the United States, and the bed of what was less than two centuries ago the largest freshwater lake in the western half of the conterminous United States.

Water, through both its presence and its absence, affects this region profoundly and in distinctive ways. The Tulare Lake Basin has a number of characteristics that make this particularly true. First, the region is close to the Pacific Ocean and thus well within range of intense oceanic storms. It has a Mediterranean climate which sees the great majority of its precipitation fall during the winter months of November through April. A further factor is that, because the region falls within the mid-thirties latitude range, it occupies the highly variable frontier between the wet winter climate of the Pacific Northwest and the often very dry winter climate of Southern California and northwestern Mexico. Adding more interest is the presence of the high-elevation terrain of the Sierra Nevada (including Mt. Whitney), which means that when the right kind of disturbances do arrive, extremely heavy precipitation can be extracted as the storms move eastward. And finally, the region’s major rivers — the Kings, Kaweah, Tule and Kern — flow into an interior basin rather than into the ocean. This last fact is true of no other significant area along the immediate Pacific Coast of the United States.

About the Author

John T Austin is a Southern farm boy who grew up and spent much of his life in the Colorado Rockies though he has now lived in the foothills of the Sierra since 1999. John earned degrees in geology, forestry, and economics. Before retiring from the National Park Service in 2014, John spent over 41 years working for that agency as a social scientist, natural scientist, planner, construction project supervisor, division chief, and program manager; all fun jobs. He spent the last part of his Park Service career working for Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks as a natural resource program manager and jack-of-all-trades.That often included working with the park’s partners in regional and watershed planning. In his spare time, he has spent the last five years researching the Tulare Lake Basin’s flood, drought, and water use history. The 500-page book that came out of that effort earned a five-star rating from Amazon. This is one of five peer-reviewed publications for which John was the sole author.

Click on the image to read 'Floods and Drought in Tulare Lake Basin' online.

Additional work from

John T Austin

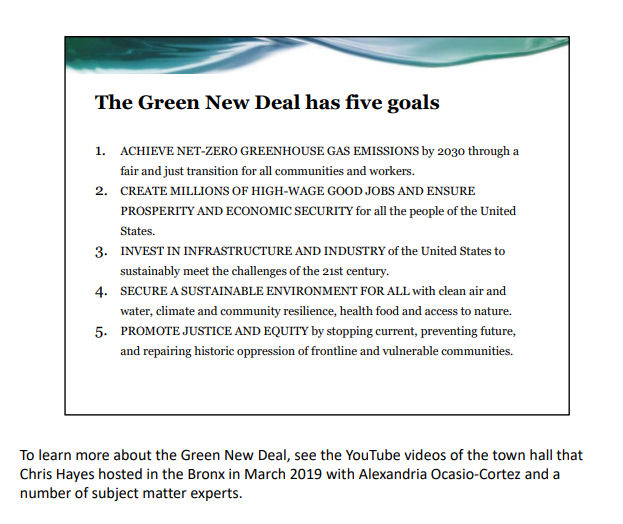

Reedley Peace Center Climate Change Presentation, April 5, 2019from the last slide of the presentation:

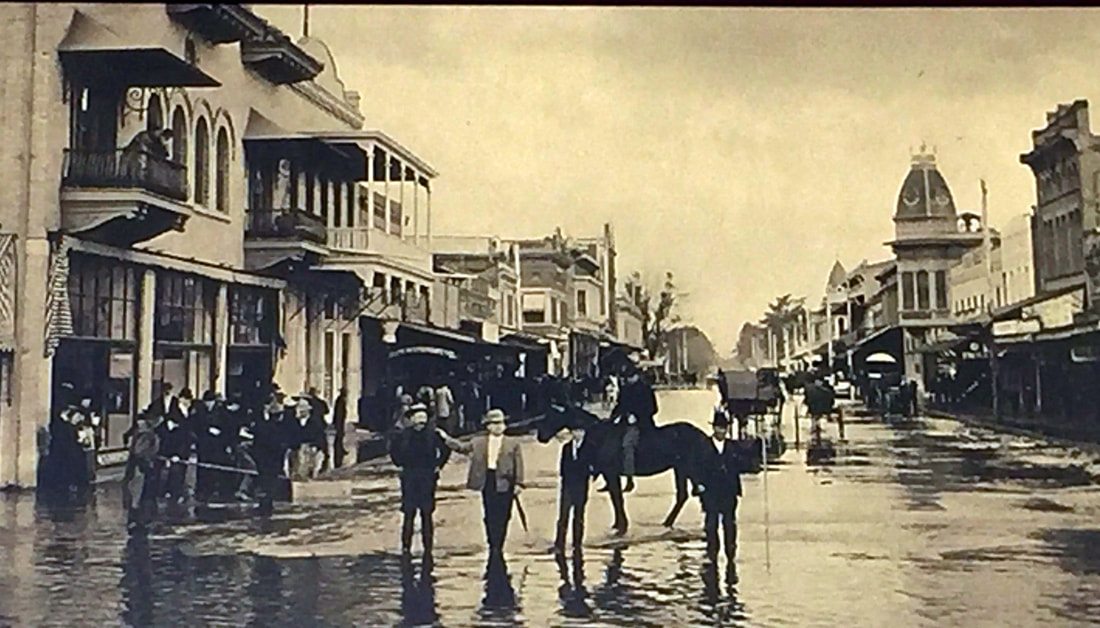

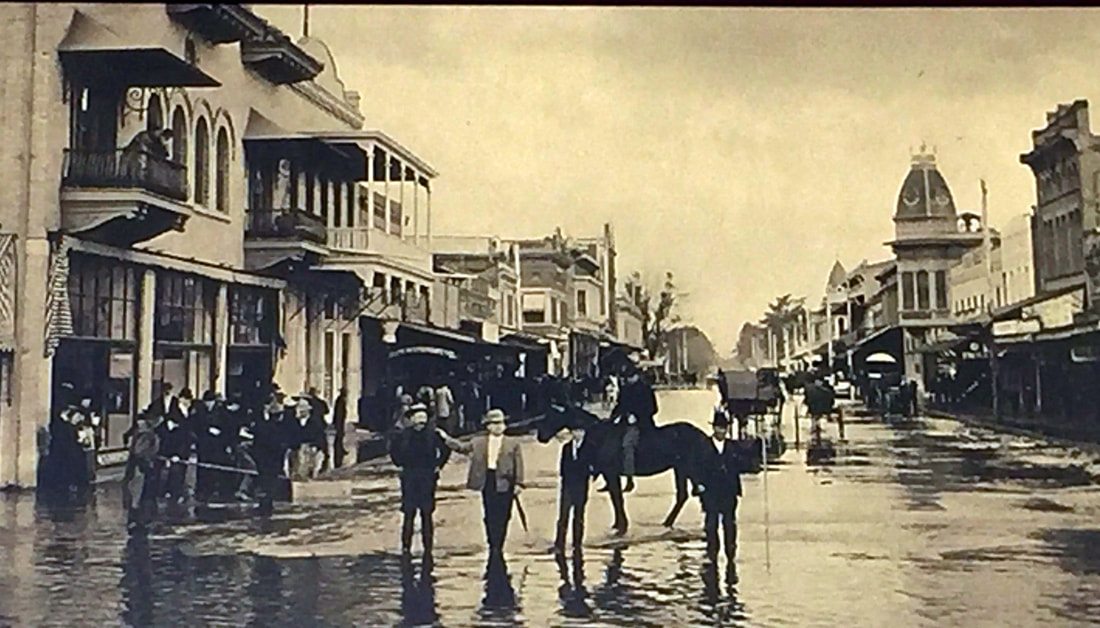

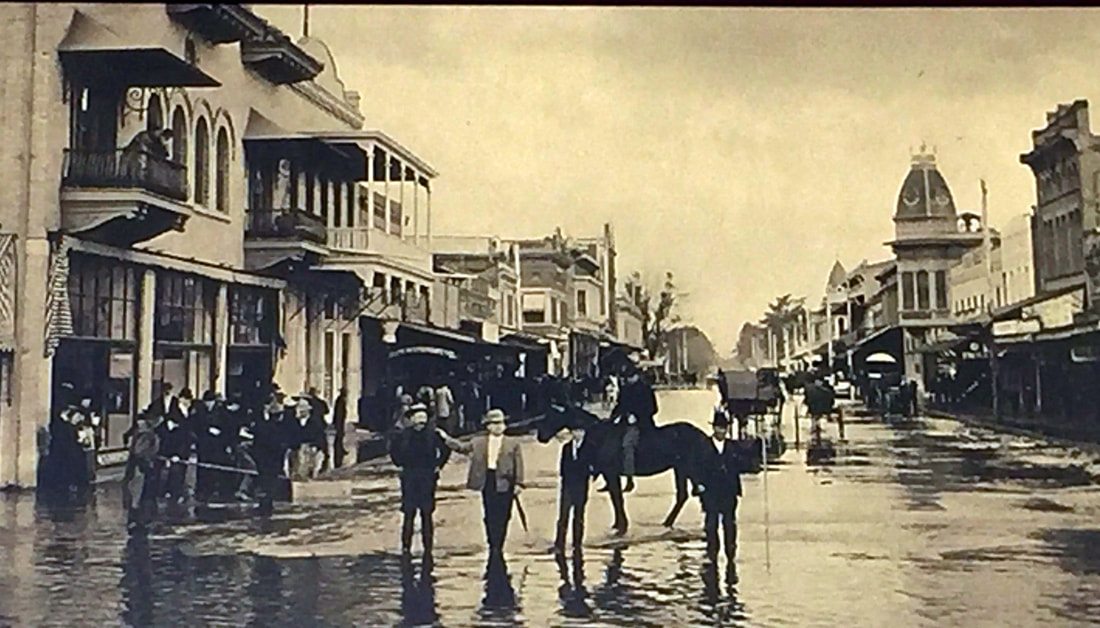

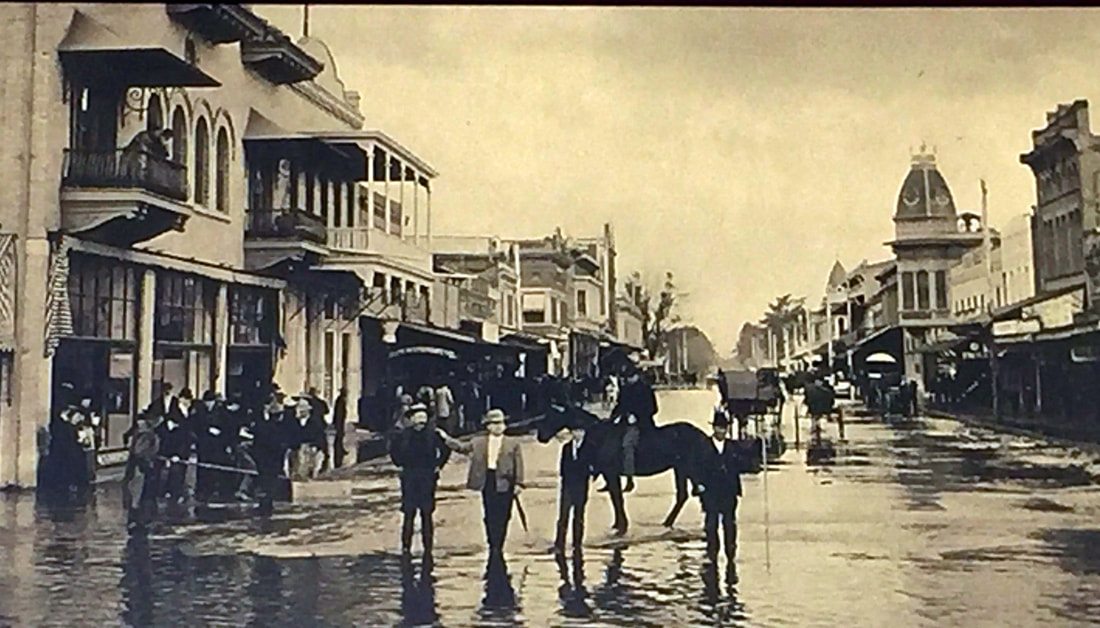

Runoff in 1906:

A revised excerpt from Floods and Droughts in Tulare Lake Basin 2nd Edition

If the May 1 projections hold (that is a very big if), total runoff in the Tulare Lake Basin for water year 2017 will be about 6.8 maf. That would make this the fourth biggest runoff year since record-keeping began in 1894. Only water years 1906 (7.2 maf), 1969 (8.4 maf), and 1983 (8.7 maf) have seen greater runoff during the instrumented period.

Three water years during the early settlement period (1853, 1862, and 1868) had enormous runoffs that would have put them in this same category (the biggest of the big), but that is a story for another day.

This is a very abbreviated story about the largely forgotten winter of 1905-06 and the associated runoff. The winter of 1905–06 was a strong El Niño event. We have a fairly good record of what occurred on the valley floor during this very wet winter; there were cities like Visalia down there that had precipitation gauges, cameras, and newspapers. But we know a lot less about what occurred in the upper watersheds...

Continue to read in full HERE.