"One Watershed" Series

|

WELCOME! The Tulare Basin Wildlife Partners has written eight One Watershed articles: #1-#7 are available via the links, and #8 appears in full below.

See past articles: OW#1: Tulare Basin Watershed 101, OW#2: Making Sense of Water, OW#3: Groundwater Management, OW#4: Native Lands, OW#5: Climate Change, OW#6: Forest Management, OW#7: Floods. #8 Water, Environmental Justice, and the Underserved of the Tulare Basin

by Dezaraye Bagalayos December 10, 2015

Before the 2011 California drought was a year old, water conditions in the Tulare Basin had already reached such critical conditions that Catarina de Albuquerque, United Nations (U.N.) representative for the Human Right to Safe Drinking Water and Sanitation, made Tulare County a focus of a UN report on the world’s water crisis hot spots.

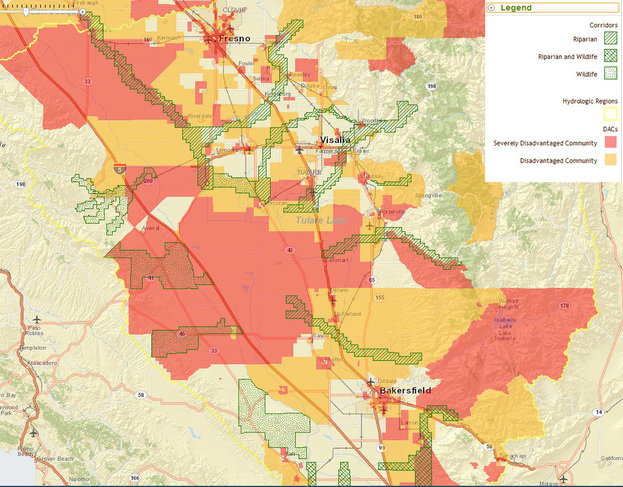

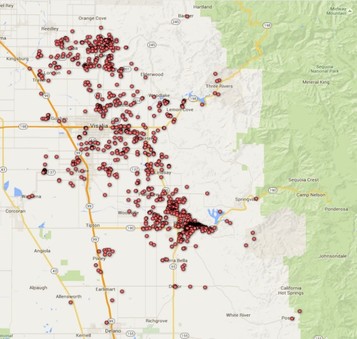

She concentrated on small, unincorporated rural communities, indicative of the Basin and its water access, quality, and infrastructure issues. Such communities, designated by the state as disadvantaged communities (DACs), are defined as having a median household income less than $48,000. In the Tulare Basin alone, there are 353 of these underserved communities, which is 67% of the Basin’s identified communities.[2] These communities are home to largely Latino populations with pockets of African American, Southeast Asian, and marginalized white households. Ms. de Albuquerque concluded in her preliminary reflections, “Problems of discrimination in U.S. water and sanitation services may intensify in the coming years with climate change and competing demands for diminishing water resources. Ensuring the right to water and sanitation for all requires a paradigm shift.” [1]  Reported Domestic Well Failures in Tulare County as of November 30, 2015 via tularecounty.ca.gov. Reported Domestic Well Failures in Tulare County as of November 30, 2015 via tularecounty.ca.gov.

Water Woes for the 67%, Drought or No Drought

Even before the current drought dried up 1,872 wells (at last count), Tulare Basin’s underserved rural communities were contending with water contamination issues: nitrate contamination on the east side of the Basin, arsenic contamination on the west side, along with harmful bacteria and other contaminants (for which there are currently no drinking water standards).[2] Finding and implementing water quality solutions is challenging because water and wastewater infrastructure is either nonexistent or so outmoded that there is strong competition for limited and sporadic funding.[3] Ryan Jensen, Community Water Center’s Solutions Coordinator, has observed significant barriers to participation in the decision-making process as well. He notes that public meetings (in these predominantly Latino communities) are usually held only in English. “Language should not be an impediment to participation but it often is. In the smallest and poorest communities, water boards are often all volunteer and not informed of their rights, how to effectively participate in regional or state decision-making processes, or how to engage community members,” Jensen said. In an October 2015 article in The Atlantic, on San Joaquin Valley’s underserved rural communities, Laura Bliss wrote, “Poor, unincorporated, predominantly non-white communities are the ones struggling…. The drought is only the newest, most visible layer in a strata of disparities.” Drought-induced well failures in rural, underserved communities reveal some of the challenges. Homeowners can apply for low interest loans to drill new or deeper holes while renters are left with short-term relief from Tulare County’s bottled water program, now serving 1,500 households.[4] The County has only recently opened its water tank program to renters with dry wells, though with strict stipulations. Despite indications of continued drought and an ever shrinking aquifer, more than 4,500 well drilling permits have been approved in Tulare County since January 2014.[4] Although California’s Sustainable Groundwater Management Act was passed in 2014, regulation enforcement begins only after 2020. As groundwater supplies are depleted, contaminants become concentrated, adding yet another layer of complexity to water quality issues.[5] This issue is a harbinger of disaster for the watershed at large because of how it affects groundwater-dependent communities and agriculture (including dairies) that have turned increasingly to groundwater. The 33% of Tulare Basin communities, generally cities located on major rivers or near the head of an aquifer, have access to surface water in most years. During a drought, when surface supplies become scarce, they turn to groundwater. Rob Hansen, a Tulare Basin biologist and educator, wonders, “When underserved communities (for whom groundwater is the principal water source), encounter drought conditions, what options are they left with?” Sandra Meraz, a longtime resident and environmental justice advocate in Alpaugh, an underserved community in southwestern Tulare County, sums up the migrant worker’s predicament, “Families are spending anywhere from 10-20% of their income on water. As a result of the drought, there is not enough work because the farmers are not hiring and the work that is available is short term, so there is not enough money going home.”  The Future: Lilah & Kyara with Deer weed and Yerba mansa at the Summer Night Lights Family Day event at Colonel Allensworth State Park in July of 2015. The Future: Lilah & Kyara with Deer weed and Yerba mansa at the Summer Night Lights Family Day event at Colonel Allensworth State Park in July of 2015.

“Do unto those downstream as you would those upstream do unto you.” – Wendell Berry

The global spotlight that the UN report shone on the water issues of Tulare Basin’s underserved rural communities combined with broad media and political attention has attracted an influx of resources and funding. Emergency Drought Funds and a portion of Proposition 1 Water Bond funds are dedicated to finding and implementing water solutions in state-identified “DACs.” Several Tulare Basin non-profits are working at the intersection of water and environmental justice to augment the state’s efforts, which are considered by many to be inadequate. Community Water Center (CWC) is a non-profit that advocates for statewide policy changes to improve water conditions in low-income communities and has a free private well testing program. Community Services Employment Training (CSET) offers free residential water bill assistance to low income households. The Central Valley Community Foundation (CVCF) is developing ways in which resources can be spring-boarded into long-term solutions by matching state and federal resource dollars with contributions from local philanthropists in order to engage communities, give them a voice, and invest in a sustainable community vision. The California Human Right to Water Bill, AB 685, was a game changer. CWC’s Regional Water Management Coordinator Kristin Dobbin explains, “None of this progress would be possible without having passed that legislation in 2012. AB 685 gives the State incentive to take bold actions and to address the ongoing crisis of water issues in California’s rural communities.” Ms. Dobbin’s colleague Ryan Jensen adds, “It has prompted a change in the culture, attitude, and prioritization at the state level with State agencies now coordinating and collaborating with non-profits and other groups working on the ground.” California Senate Bill 88 authorizes the State Water Resources Control Board to institute public water system consolidations to water-stressed disadvantaged unincorporated communities. The underserved communities of Allensworth and Alpaugh are poised to serve as a pilot project and example for “alternative” consolidation where one option being considered is managerial and/or operational support resource sharing. Allensworth advocate and resident Denise Kadara clarifies that regional solutions are the focus: “Allensworth has water issues and Alpaugh has water issues. The solution rests in coming together and consolidating in a mutually beneficial way that makes sense for both communities.” Sandra Meraz of Alpaugh agrees, “Consolidation is the proper thing to do. Education, health, and safety all boil down to water.” Denise Kadara works on community-building with a focus on youth leadership and environmental justice. “We have an ideal opportunity to work with the youth in the community. The earlier you can mentor, educate, and expose the youth to environmental work and how to advocate on behalf of their homes, the sooner they grow roots and begin to be part of the solution instead of part of the problem.” Shifting waters In her 2013 report to the U.N. Human Rights Council General Assembly, Catarina de Albuquerque noted that “common approaches to water and sanitation often fail to incorporate sustainability,” perpetuating the problem of water insecurity, especially among the world’s poorest communities. [1] Underserved, rural communities within the Tulare Basin are an immediate and proximal “canary in a coal mine” of the effects that environmental degradation and climate change can have on our region. They also stand as the incubators for collaborative, forward thinking, and sustainable solutions for environmental issues faced throughout the state and around the world. The paradigm shift toward holistic thinking and connective problem-solving is underway with our underserved, rural communities poised to set the standard for achieving long-term, sustainable solutions on a watershed level and worldwide. -- Resources: [1] Catarina de Albuquerque’s Preliminary Reflections, Press Statement from the United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner March 2011 [2] Disadvantaged Community Water Study for the Tulare Lake Basin Final Report August 2014, p.21 & p.36 [3] The Atlantic, “Before California's Drought, a Century of Disparity” October 2015 [4] Tulare County Drought Effects Status Updates [5] Water in the West,”The Hidden Costs of Groundwater Overdraft “ September 2014, p.4 Authored by Dezaraye Bagalayos is the Program Coordinator for the Tulare Basin Wildlife Partners and Tulare Basin Watershed Initiative.

|

Mission: To raise awareness about the Tulare Lake Watershed and its unique attributes, challenges, and opportunities. From the snowy peaks to the valley floor, we are one watershed.

This project is made possible through grant funding from the Central Valley Community Foundation, formerly the Fresno Regional Foundation.

This project is part of the Tulare Basin Watershed Initiative.

HELPFUL LINKS:

|